The Island of Vieques After Hurricane Maria’s Devastation in the Caribbean

A Plan to Storm Proof the Island of Vieques Through Advanced Ecological Design and Social Innovation: A Way Forward

by John Todd

The summer of 2017 was a season of intense storms. Hurricane Harvey flooded Houston and Irma left a path of devastation across the Caribbean and Florida. Hurricane Maria crippled Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. The Island of Vieques, just offshore of the eastern end of Puerto Rico, was flattened and the devastation was almost incomprehensible. Global climate change is destabilizing the weather widely around the world. A pattern of increasing storm intensity due to the warming of seawater is emerging. Higher temperatures cause the winds to become stronger and more damaging. Their destructive power increases exponentially with speed. Winds of 125 miles per hour inflict twice the damage as those of 100 miles per hour winds. Storm intensification is further compounded as rising sea temperatures increase moisture in the atmosphere, leading to more rainfall and flooding. A less discussed, but equally important phenomenon, are the winds and salt laden rains. They reap ecological havoc. The resulting downed trees, uprooted shrubs, and lost soils seriously affected the overall ecology and the biological underpinnings of the region become very fragile. Without intact ecosystems the social infrastructure can be weakened as well. Before hurricane Maria, Vieques was totally dependent on Puerto Rico for its water, food, electricity and fuel as well as its transportation. After the storm their umbilical chord from Puerto Rico was cut off. For months the residents endured real suffering and for some, death.

A Vision of the Future for the Island of Vieques

Imagine if you will, a bold new plan for the island unfolding. It is sustained through an ecological design revolution that links all of the diverse elements of the island and its communities into a comprehensive whole. The whole is robust and self-organizing and very inclusive. Life-giving rainwater is carefully harvested from roof-tops and stored for drinking for both people and livestock. It is also used to irrigate gardens and for food processing enterprises. These water capture methods have been developed technologically and tested in several places around the world, including Mexico. Water security is at the top of the community’s priority list.

Another dramatic change that sets the island apart from others in the Caribbean is the landscape. It has been storm proofed through the creation of new landforms that blunt the wind. Mounds and hillocks have been planted to vegetation that can withstand fierce winds and salt laden air. Flexible bamboos serving as excellent windbreaks are integral to the plantings. Resident ecologists and architects have borrowed concepts and techniques that have been proven over centuries in typhoon prone areas of Japan. Reforestation of much of Vieques has begun. Plantings of native trees and fruit, nut, fodder and timber trees have already been established. Along the shore and in coves mangroves have been planted for coastal protection and for woody biomass. It is hoped that the new vegetation will also help protect and restore the surrounding coral reefs. The island’s new Center for Applied Ecology has started a seed bank of native plants of the Caribbean. Their newly established nursery is a favorite destination on the island.

Following Hurricane Maria the island’s wastewater could not be treated and sewage backed up creating a health risk. It was realized that wastewater treatment as practiced is totally dependent on the old and failed infrastructure. A new green hotel, being developed, decided to lead the way by adopting a green technology known as an ecomachine to purify the sewage and recycle the water to support its diverse landscape.

Vividly remembering their hunger and not having much in the way of food as well as water for several months, has led to a program of food self-sufficiency. New farms are beginning to be established utilizing methods suited to the trop - ics and for protection from tropical storms. The farm school is a favorite educational resource for young islanders. They feel useful, as they are paid in produce that they bring home to their families. Another project that might prove important, is an initiative to investigate plants called halophytes. Halophytes can grow in conditions of elevated salt levels in soils that can occur after tropical storms. A major attribute of halophytes is their ability to utilize inorganic ions such as Na+ and Cl- major components of salt water. As a consequence they can grow where most plants cannot and help to restore saline and contaminated lands. The best known halophyte may well be Quinoa, a fashion - able and healthy gluten free edible grain.

There is a lot of excitement around a new project initiated by the Center for Applied Ecology. It is a saltwater farm. It is designed to combat two threats and to open up a new economy for the island. The first of these threats is sea level rise. The second is hurricanes and tropical storms that would destroy conventional systems developed for farming in the sea. Their plan is to build a tank-based saltwater farm above and away from the reach of storm surges on land. The system will be further protected by a series of wind deflect - ing berms. Using solar energy, salt water will be pumped, from the sea to the farm. Seawater that is contaminated with wastes from growing fishes and other aquatic organisms will be highly treat - ed in a green technology that uses mangroves to clean and filter the water. Mangroves will be periodically harvested for biomass including timber. The Center has already established a small prototype ecosystem grows edible fish, tropical shrimp, oysters and clams. They also grow supplemental feeds for the shrimp. Although it is small, it is state of the art ecological design.

During the hurricane Vieques lost its electrical power from Puerto Rico. To compound the problem there was little fuel for standby back-up power. A decision was subsequently made to begin the process of making the island completely dependent upon renewable energy, most notably, but not completely, based upon solar panels. For redundancy and backup the rugged solar farms were scattered throughout the island. Individual houses and buildings installed smaller roof-based solar systems to provide power to protect foods and medicines during emergencies. The planned new medical center is powered by solar energy with backup electrical storage capabilities. With renewable energy the islanders began to feel more confident about their future no matter what the weather might bring.

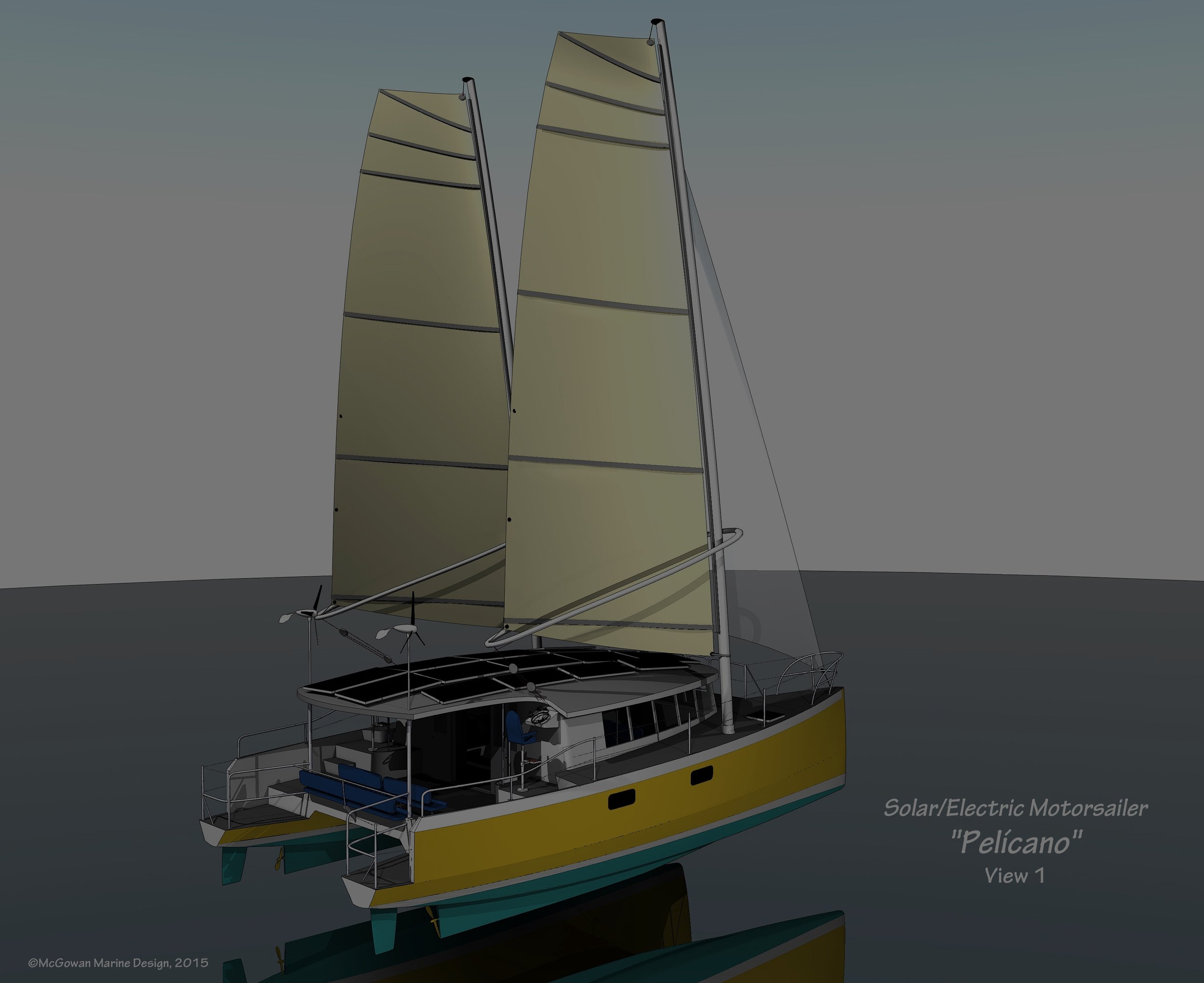

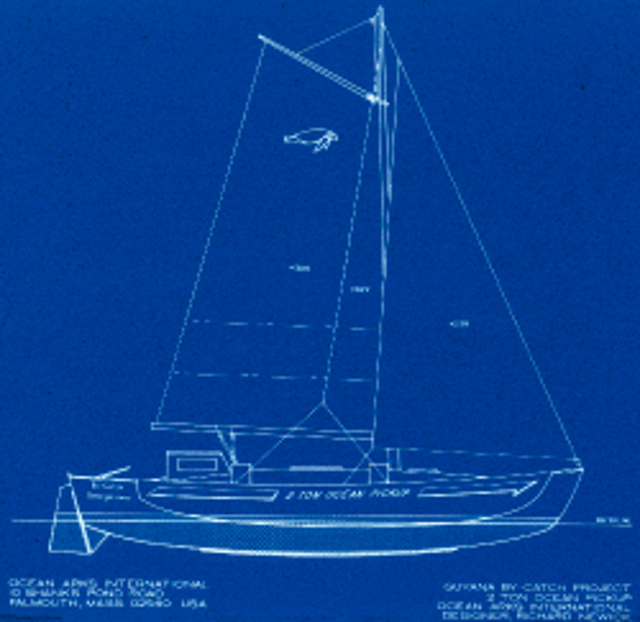

Fuel had been a major problem during the post hurricane period. It was unavailable and fishermen whose boats survived the storm were not able to put to sea. An initiative was started by the Center for Applied Ecology. They began to develop sea transportation that was renewable energy based. The Caribbean is seriously hampered by its dependency on ocean transportation and cargo vessels that were derived from oil rig support vessels. They are fuel inefficient and very expensive to build and maintain. Compared to mainlanders islanders have paid much more for basic goods for years. Airfreight too is expensive. The Center’s plan was to design and build a new kind of carbon neutral ocean transportation on the island. Working with a Canadian naval architect, Laurie McGowan, they set to work developing a wind and solar powered watercraft that would be energy independent. Pelicano, a catamaran, is designed to be used as an inter-island transportation vessel, excursion boat, light cargo, fishing and a tourist dive boat. The Center is exploring the best way to create an island-based infrastructure to build a small fleet of these vessels. The Center’s foresters have already developed techniques to make composite boat building materials from fast growing trees on the island.

An unprecedented sense of possibility is beginning to characterize the Island. A diverse economy is being created that includes a thriving tourism, growing agriculture and aquaculture, its own energy and transportation initiatives and educational initiatives and opportunities rarely seen on small islands. A sense of stability and hope is in the air. It is a vision for the future. The real challenge ahead is to transform these ideas into reality.

From Vision to Reality: A Path Forward

The guiding light behind the vision for Vieques is a New York based Italian architect Roberto Brambilla. He is widely experienced with successful projects in New York and throughout the Mediterranean. Over fifteen years ago he visited Vieques and he fell in love with the island. He bought some land for a planned resort and hosted a team of ecological design experts to plan an infrastructure that was highly adapted to conditions there. Progress with his plan was slow and included a series of legal and financial hurdles. But he persisted.

After Hurricane Maria, Roberto Brambilla renewed his efforts to assist the island. He connected with like-minded people committed to helping the island. Subsequently he concluded that a strictly commercial model for development was inadequate to the task. He proposed that the whole plan should develop under the umbrella of a not-for-profit foundation. He chose the Art and Landscape Foundation. His own major development project, known as the Soft Hotel, was to be brought in under the non-profit umbrella. A plan emerged to seek startup capital and resources from philanthropic organizations.

The current plan is to employ Ocean Arks International, a 501 c-3 non-profit based in Massachusetts, to oversee the ecological redesign of the Soft Hotel, the storm proofing of the island and a technical school for islanders to get skills training in the rebuilding of the island. Ocean Arks International has worked throughout the world for the last thirty-seven years and has pioneered living technologies to solve infrastructure issues.

Under review is an idea to form a cooperative that serves the island. Cooperatives are used widely throughout the US as organizations that provide financing, education and a variety of services. They are at the heart of natural resources development in a number of midwestern states The legal basis for Cooperatives was created by the Capper-Volstrand Act in 1926. They are democratically run. Each member of the coop has only one vote. Federal law limits annual returns to 8%. Cooperatives can secure capital through the Farm Credit System which currently provides about three hundred billion dollars of loans, leases and related services. There are also rural electrical cooperatives funded with help from the Federal government through the Department of Energy. Cooperatives can provide marketing, purchasing and community educational services. They should be given serious consideration as facilitating entities for Vieques.

What is proposed here is a bold step forward. We expect that the project can be established with an initial investment of ten million dollars. The alternative, the old way, is simply not adequate enough to cope with the twin threats of increasingly severe storms and rising sea levels. Comprehensive ecological design may turn out to be the only economical way forward for most of the islands of the Caribbean.

Article from Annals of Earth : Volume XXXV, Number 2, 2017